ScrabbleCV - Real-time Mobile Scrabble Scoring via Computer Vision and Neural Networks

Contents

- Introduction

- Architecture Overview

- Board Parsing Pipeline

- Scoring

- Android Implementation

- Training

- Gameplay

- Prior Approaches

- Constraints

- Future Work

- Conclusion

Introduction

Scoring Scrabble by hand is slow and can be prone to errors. ScrabbleCV is an Android app that uses computer vision and neural networks to score a turn from a single image.

Architecture Overview

At a high level the system has two main parts:

- Board Parsing - turns camera frames into a 15 x 15 grid of letter placements.

- Scoring Engine - validates word placements, determines scored word(s), and applies multipliers.

Board Parsing Pipeline

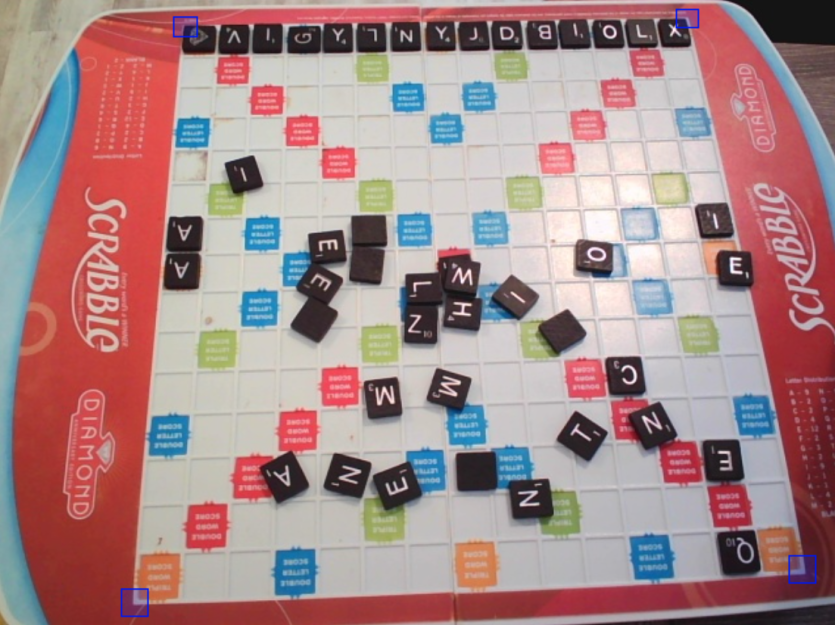

Extracting the board state requires locating and classifying tiles. To do so, a clear board image is necessary.

Detect Corners

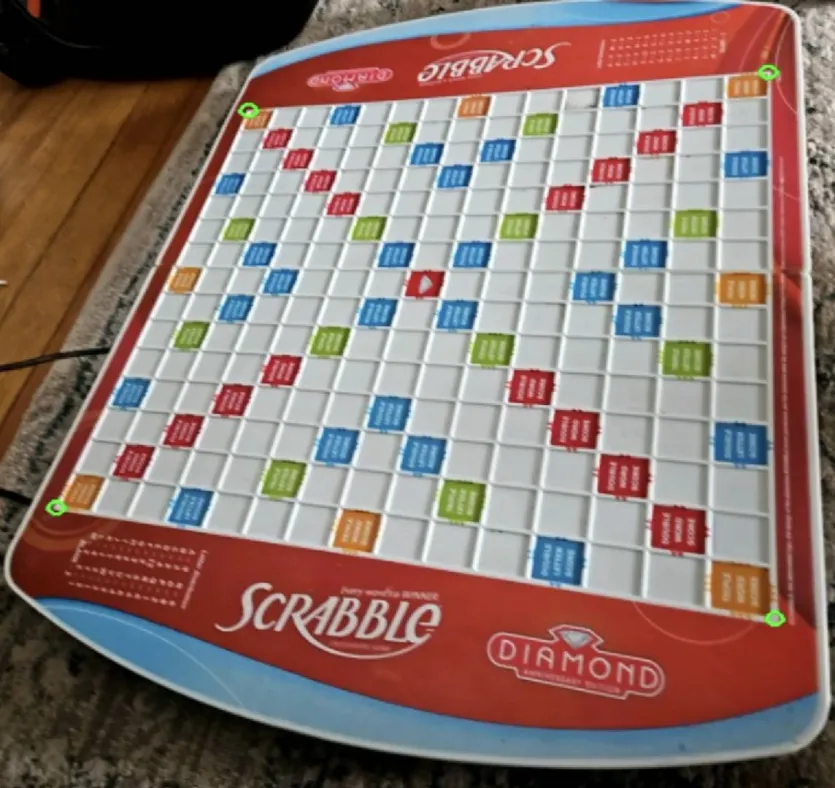

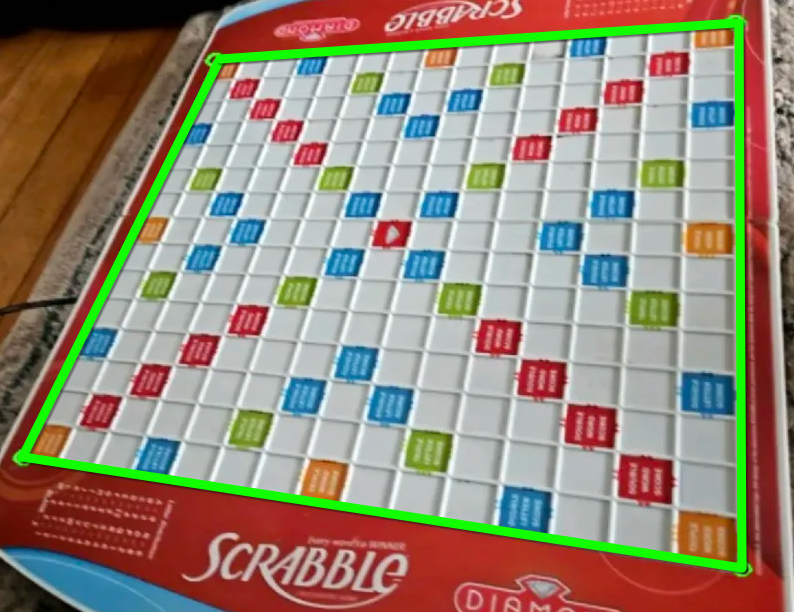

Detecting the board’s corners isolates the play area regardless of perspective, rotation, or distance. The four detected corners form a convex quadrilateral, defining the borders of the playable board [see Figure 0]. These vertices are used to calculate a perspective transform matrix, which when applied to the original image creates a top-down, uniform view of the tiled area. [see Figure 1].

YOLOv10

Corner detection was implemented using YOLOv10 nano (Training), a lightweight variant of the YOLOv10 object detection architecture for mobile and edge devices. YOLO (You Only Look Once) models are a family of convolutional neural networks designed for real-time object detection. These networks can detect and classify multiple objects in an image with a single pass through the network, outputting bounding box coordinates and confidence scores for each object.

Each object detection model, including YOLO, all have different architectural tradeoffs which can vary results between use-cases. YOLOv10 was chosen in corner detection for a few reasons.

Availability and Accessibility

- YOLO models lead the way in applications for real world systems due to their prevalence in computer vision libraries. Ultralytics is a python library that streamlines the process for training YOLO networks.

NMS-Free Detection

- Previous YOLO models, such as YOLOv8, use an algorithm called Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) to reduce overlapping bounding boxes to a single area. These models output a large list of potential boxes for each object, and this algorithm is necessary to reduce and merge them. YOLOv10 introduces a dual head head architecture using a One-to-Many head, which produces many predictions and One-to-One head which produces a single, high quality prediction. These predictions are joined together via Hungarian matching during removing the need for NMS. Previous architectures, such as YOLOv8, output thousands of potential bounding boxes that need to be decoded. YOLOv10 only generates a few hundred without the need for any merging. Skipping the need for NMS reduces computational load on the CPU, allowing parallelized efficiency gains by allocating more to the GPU.

Lite Runtime (LiteRT)

LiteRT, previously known as Tensorflow Lite, is a highly optimized deep learning inference runtime for mobile and edge applications. LiteRT was chosen over other runtimes due to challenges described in Prior Approaches. An optimized runtime such as LiteRT provides control when running neural networks on-device, such as offloading operations to CPU/GPU.

Inference

Once a camera stream is opened, the corner detection begins. Before an image can be passed into the neural network, it must be pre-processed. First, an image is resized to 640x640 and pixel values are normalized from an integer value of 0-255 to a floating point value 0-1. These are properties the network expects, as each improves the training results.

Following pre-processing, the image is passed through the model. The YOLOv10 architecture returns a list of 300 elements, each a potential bounding box, sorted in the list via the confidence score. A minor amount of post-processing is still necessary to extract the desired (x, y) coordinate points for each corner of the board.

Corner Filtering

As mentioned in (Training Corners), images are labelled with a tightly fitting bounding box, with each corner of the board in the center of a bounding box. Because of this, the center of the network’s output bounding boxes can be used as the coordinates for the corner.

Initially, a threshold of 0.6 was used to remove low-confidence predictions, taking the four most confident coordinates as the suggested corners of the board. However, poor lighting conditions or awkward camera angles cause lower confidence scores, leading to missed detections. While YOLOv10’s new approach mentioned in Direct coordinate network output avoids overlapping outputs, nearby, non-overlapping bounding boxes aren’t prevented. These boxes cannot be weeded out by an exclusively thresholding approach either. Multiple sets of coordinates can still be detected for a particular corner. This prevents a 5th, slightly lower confidence detection from being placed to a valid, unlabelled corner.

To solve this, a low threshold of 0.03 is used, encouraging many detections to pass through. Clusters of detections add redundancy, catching potential low confidence corners. For each point in these clusters, proximate detections are reduced to a single point. From the remaining isolated detections, the top four confidence points are taken as the true corners.

The following is the Java code that was used to perform the cluster filtering:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

private static List<Point> getTrueCorners(List<Detection> detections) {

List<Detection> filtered = new ArrayList<>();

int PX_FILTER_DIST_SQ = 300;

float CONFIDENCE_THRESH = 0.03f;

// Filter detections by confidence and proximity

for (Detection det : detections) {

int centerX = Math.round(det.x1 + (det.x2 - det.x1) / 2.0f);

int centerY = Math.round(det.y1 + (det.y2 - det.y1) / 2.0f);

boolean tooClose = false;

// Threshold the euclidean distance of the current detection and the filtered ones.

for (Detection kept : filtered) {

int keptX = Math.round(kept.x1 + (kept.x2 - kept.x1) / 2.0f);

int keptY = Math.round(kept.y1 + (kept.y2 - kept.y1) / 2.0f);

int dx = centerX - keptX;

int dy = centerY - keptY;

if ((dx * dx + dy * dy) <= PX_FILTER_DIST_SQ) {

tooClose = true;

break;

}

}

// Only keep the detections that are confident and not too close to each other.

if (det.confidence >= CONFIDENCE_THRESH && !tooClose) {

filtered.add(det);

}

}

int limit = Math.min(4, filtered.size()); // Keep 4 corners w/highest confidence

List<Point> corners = new ArrayList<>(limit);

for (int i = 0; i < limit; i++) {

Detection det = filtered.get(i);

int centerX = Math.round(det.x1 + (det.x2 - det.x1) / 2.0f);

int centerY = Math.round(det.y1 + (det.y2 - det.y1) / 2.0f);

corners.add(new Point(centerX, centerY));

}

return corners;

}

}

Board Validation

Once 4 potential corners are identified, there are more constraints that can be applied to void an invalid board from improper detections.

From any perspective, the true corners of a board form a convex quadrilateral. Because of this, we can invalidate any set of corners that does not follow this rule. In any case, none of the vertices can exceed an angle of 180 degrees.[see Figure 1]

Similar to before, squared euclidean distance can also be used to enforce a minimum distance between corners.

The following code enforces convex quadrilateral and minimum corner distance checks:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

private boolean checkCorners(List<Point> corners) {

...

// Convex quadrilateral check

if (!(theta_tr <= 130 && // top right vertex

theta_br <= 130 && // bottom right vertex

theta_bl <= 130 && // bottom left vertex

theta_tl <= 130)) // top left vertex

{

return false;

}

...

// Check minumum corner distance

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

for (int j = i + 1; j < 4; j++) {

Point a = corners.get(i);

Point b = corners.get(j);

double dx = a.x - b.x;

double dy = a.y - b.y;

if ((dx * dx + dy * dy) < MIN_PX_DIST_SQ) return false;

}

}

return true;

}

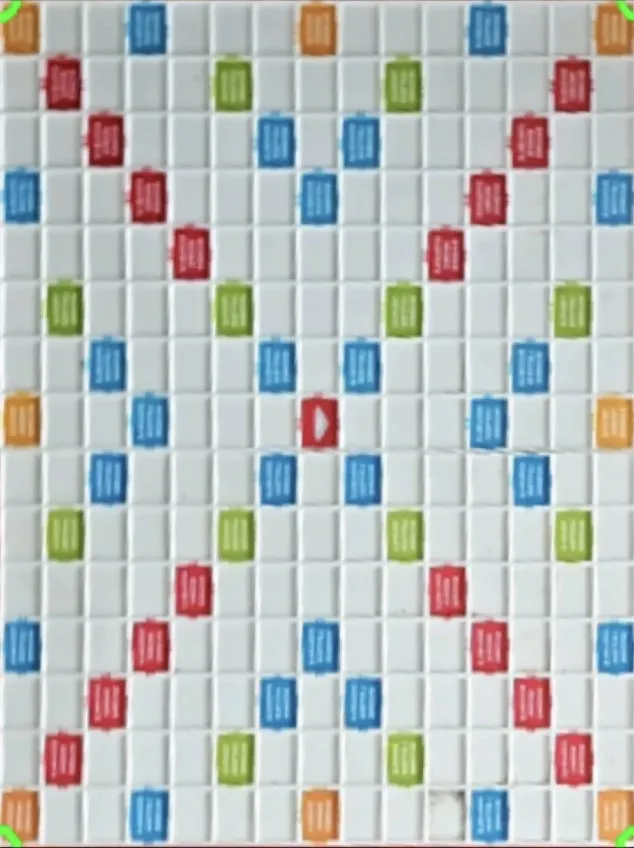

Transform Board to Top-Down View

Using the 4 corners of the board we can warp the perspective of the board to align the board’s cells in a uniform manner. The following code contains the logic used in the transform.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

def orient_board(input_image, corners):

# First, we determine the extreme points in each direction

sums = [x + y for (x, y) in corners] # top-left has smallest sum, bottom-right largest

diffs = [x - y for (x, y) in corners] # top-right has smallest difference, bottom-left largest

top_left = corners[np.argmin(sums)]

top_right = corners[np.argmin(diffs)]

bot_right = corners[np.argmax(sums)]

bot_left = corners[np.argmax(diffs)]

# Source points from the original image

src_pts = np.array([top_left, bot_left, bot_right, top_right], dtype=np.float32)

# Destination points, desired locations after warp

dst_pts = np.array([

[0, 0],

[639, 0],

[639, 639],

[0, 639]

], dtype=np.float32)

# Create and apply perspective transform matrix from source to destination

M = cv2.getPerspectiveTransform(src_pts, dst_pts)

warped = cv2.warpPerspective((input_image).astype(np.float32), M, (640, 640))

return warped

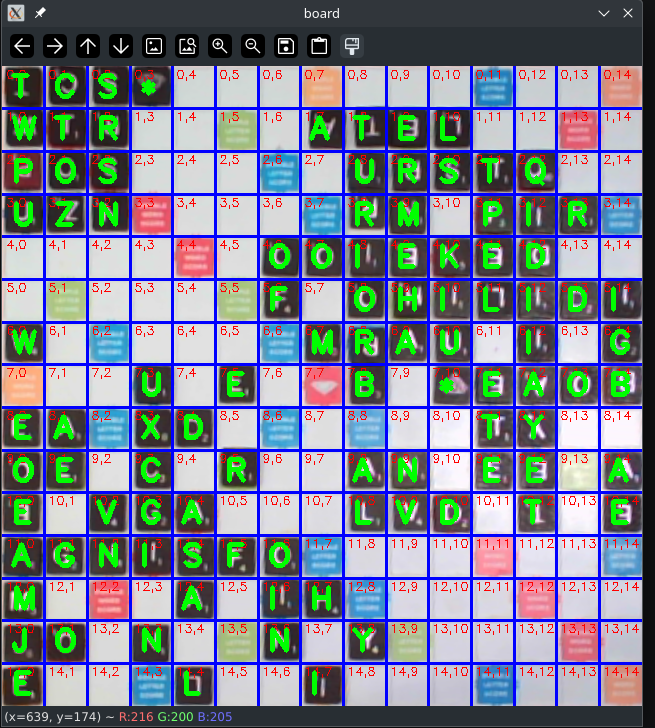

Classify Tiles

After a valid, top-down view of the board is produced, the tile classification process can begin.

Extract Placed Tiles

Performing classification on cells that do not contain a tile is a wasted operation. A window of size 42x42 iterates over all of the cells in the image. The cell image is then color thresholded to determine the placed tiles. Since only black tiles are used, if a certain percentage of the cell image contains a dark color, then it can be assumed that there is a tile present. Cell images that contain a tile are saved for further classification. The following logic is the color thresholding applied to each cell.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

r, g, b = (60, 60, 60)

target_color = np.array([r, g, b])

tol = np.array([60, 60, 60])

lower = np.clip(target_color - tol, 0, 255)

upper = np.clip(target_color + tol, 0, 255)

mask = cv2.inRange(cells[cell_idx], lower, upper)

coverage = np.count_nonzero(mask) / mask.size

if coverage > 0.5:

filled_cells.append(cell_idx)

Convolutional Neural Network Classification

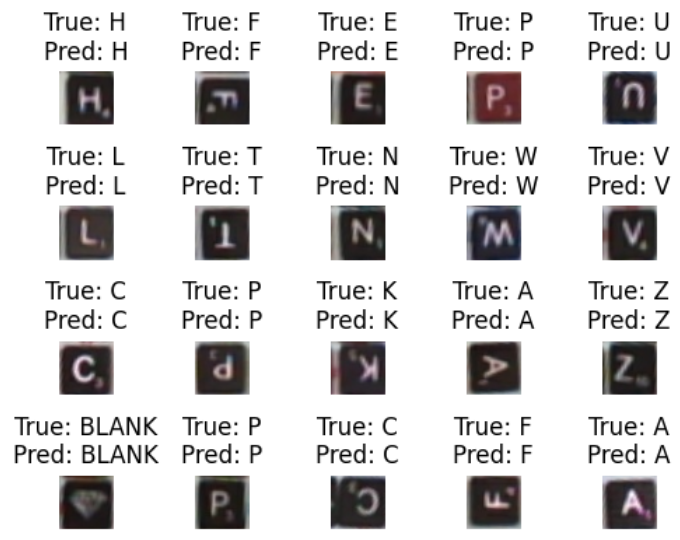

Each 42x42 image that contains a tile is processed through a small convolutional neural network (CNN) that classifies it between 27 classes (A-Z, Blank). (Training)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

inputs = keras.Input(shape=input_shape)

# Conv2D, ReLU activations, and MaxPooling2D layers extract meaningful features

# about the input image. Successive layers will contain higher level features,

# such as curves, o's, or lines.

x = layers.Conv2D(32, kernel_size=(5, 5), activation="relu")(inputs)

x = layers.MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2, 2))(x)

x = layers.Conv2D(64, kernel_size=(3, 3), activation="relu")(x)

x = layers.MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2, 2))(x)

x = layers.Conv2D(128, kernel_size=(3, 3), activation="relu")(x)

x = layers.MaxPooling2D(pool_size=(2, 2))(x)

# GlobalAveragePooling2D averages feature maps of each channel, resulting with a 1D tensor.

x = layers.GlobalAveragePooling2D()(x)

# Dropout helps prevent overfitting by disabling a random set of neurons during

# training, forcing the model to learn a more robust representation of the data.

x = layers.Dropout(0.3)(x)

# Dense layer with ReLU activation classifies the features extracted from the

# preceding layers.

x = layers.Dense(256, activation="relu")(x)

# A final Dense layer classifies the learned representation, and a softmax activation

# normalizes the output vector into 0-1 where all values sum to 1. The determined classification

# has the highest value in the output tensor, where the index of the highest output value is the

# value that the network predicts.

outputs = layers.Dense(num_classes, activation="softmax")(x)

The index with the highest confidence in the CNN output (ranging from 0 to 26, corresponding to ['A', ..., 'Z', '*']) is incremented by 1 before being stored in the board state array. Empty cells are represented with an integer 0, and character value ‘_’.

1

2

3

4

private static final String[] CLASS_NAMES = {

"_","A","B","C","D","E","F","G","H","I","J","K","L","M","N","O",

"P","Q","R","S","T","U","V","W","X","Y","Z","*"

};

Scoring Engine

Tracking Player Moves

Accurately identifying the tiles placed by each player is necessary for scoring and enforcing legal moves. To do this, the system must compare the current board state to the previous one and extract the newly placed tiles. However, since players can capture an image of the board from any orientation, including 90°, 180°, or 270°, the system must account for arbitrary rotations to correctly align and compare the two board states.

A solution for this requires maintaining a mask of the previous move, a matrix of the same board dimension with a 0 for cells with no tile, and 1 for those containing a tile. The current matrix of the board state can be rotated and multiplied with the previous mask. When the rotated matrix is equal to the previous board state matrix, the new word can be extracted. Exclusive OR between the current and previous boards can be used to extract a mask of the newly placed tiles.

The following is the code used to track the board state:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

turnCnt = getTurnCount();

currBoard = safeCopy(getBoardState(), 225);

currMask = safeCopy(getBoardMask(), 225);

newBoard = safeCopy(getNewBoardState(), 225);

newMask = safeCopy(getNewBoardMask(), 225);

rotNewBoard = Arrays.copyOf(newBoard, 225);

rotNewMask = Arrays.copyOf(newMask, 225);

result = new int[currMask.length];

newTilesMask = new int[currMask.length];

newTiles = new int[currMask.length];

// No need to match orientation for the first move

if (turnCnt == 0) {

if (newBoard[7 * 15 + 7] == 0) { // A tile must be placed on the center of the board

return false;

} else {

newTiles = newBoard.clone();

newTilesMask = newMask.clone();

}

} else {

int sz = 15;

// Finding matching orientation

for (int rot = 0; rot < 4; rot++) {

newTilesMask = new int[currMask.length];

newTiles = new int[currMask.length];

// Do not rotate for 0

if (rot != 0) {

for (int i = 0; i < sz; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < sz; j++) {

int idx = (i * sz) + j;

int idx_rot = (j * sz) + (sz - i - 1);

rotNewBoard[idx_rot] = rotNewBoard[idx];

rotNewMask[idx_rot] = rotNewMask[idx];

}

}

}

for (int i = 0; i < currBoard.length; i++) {

result[i] = rotNewBoard[i] * currMask[i]; // get previous board state

newTilesMask[i] = rotNewMask[i] ^ currMask[i]; // get mask of new tiles

newTiles[i] = rotNewBoard[i] * newTilesMask[i]; // get new tiles

}

if (Arrays.equals(result, currBoard)) {

break;

} else if (rot == 3) {

return false; // if 3 rotations and no match, something is not right

}

}

}

The next step after getting an array with the most recently played tiles is to determine all of the connecting words the indicies of their cells.

First, the board is scanned row by row to identify horizontal sequences of tiles. A “run” begins when a non-empty cell is found and ends when an empty cell or the row boundary is reached. If the run is at least two tiles long and contains at least one newly placed tile (per the new tile mask), its indices are added to the list of word candidates. After completing the horizontal pass, the same logic is applied column by column to detect vertical word runs. A list of the indices of each of the word sequences is returned.

The following code implements the processed described above, extracting the indices of the tiles to be scored.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

public List<int[]> extractWordIndices() {

List<int[]> found = new ArrayList<>();

int sz = 15;

// HORIZONTALS

for (int r = 0; r < sz; r++) {

int runStart = -1;

boolean sawNew = false;

for (int c = 0; c <= sz; c++) {

boolean occupied = (c < sz && rotNewBoard[r*sz + c] != 0);

if (occupied) {

if (runStart < 0) {

runStart = c;

sawNew = (newTilesMask[r*sz + c] == 1);

} else if (newTilesMask[r*sz + c] == 1) {

sawNew = true;

}

}

if (!occupied && runStart >= 0) {

int runLen = c - runStart;

if (runLen > 1 && sawNew) {

int[] cells = new int[runLen];

for (int j = 0; j < runLen; j++)

cells[j] = r*sz + (runStart + j);

found.add(cells);

}

runStart = -1;

}

}

}

// VERTICALS - same idea, swap r/c

for (int c = 0; c < sz; c++) {

int runStart = -1;

boolean sawNew = false;

for (int r = 0; r <= sz; r++) {

boolean occupied = (r < sz && rotNewBoard[r*sz + c] != 0);

if (occupied) {

if (runStart < 0) {

runStart = r;

sawNew = (newTilesMask[r*sz + c] == 1);

} else if (newTilesMask[r*sz + c] == 1) {

sawNew = true;

}

}

if (!occupied && runStart >= 0) {

int runLen = r - runStart;

if (runLen > 1 && sawNew) {

int[] cells = new int[runLen];

for (int i = 0; i < runLen; i++)

cells[i] = (runStart + i)*sz + c;

found.add(cells);

}

runStart = -1;

}

}

}

return found;

}

Scoring

The scoring logic determines the total points for a move by iterating over each extracted word. For each word, the individual letter scores are calculated with the tile’s value, as well as any letter multiplier. Sequences are summed, and any word multipliers are then applied. Multipliers are only applied to newly place tiles, and looked up from hardcoded 15x15 arrays corresponding to a standard board layout. Words are then summed and a bingo bonus is applied if 7 tiles are placed.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

final int SZ = 15;

List<int[]> words = extractWordIndices();

Log.d(TAG, words.toString());

int total = 0;

for (int w = 0; w < words.size(); ++w) {

int[] wordCells = words.get(w);

int wordSum = 0;

int wordMul = 1;

for (int k = 0; k < wordCells.length; ++k) {

int idx = wordCells[k];

int r = idx / SZ;

int c = idx % SZ;

int letter = rotNewBoard[idx];

int pts = LETTER_POINTS[letter];

// Multipliers only apply to newly placed tiles

if (newTilesMask[idx] == 1) {

pts *= Lmult[r][c]; // DL / TL

wordMul *= Wmult[r][c]; // DW / TW

}

wordSum += pts;

}

total += wordSum * wordMul;

}

// Bingo

int tilesUsed = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < newTilesMask.length; ++i)

tilesUsed += newTilesMask[i];

if (tilesUsed == 7) total += 50;

Android Implementation

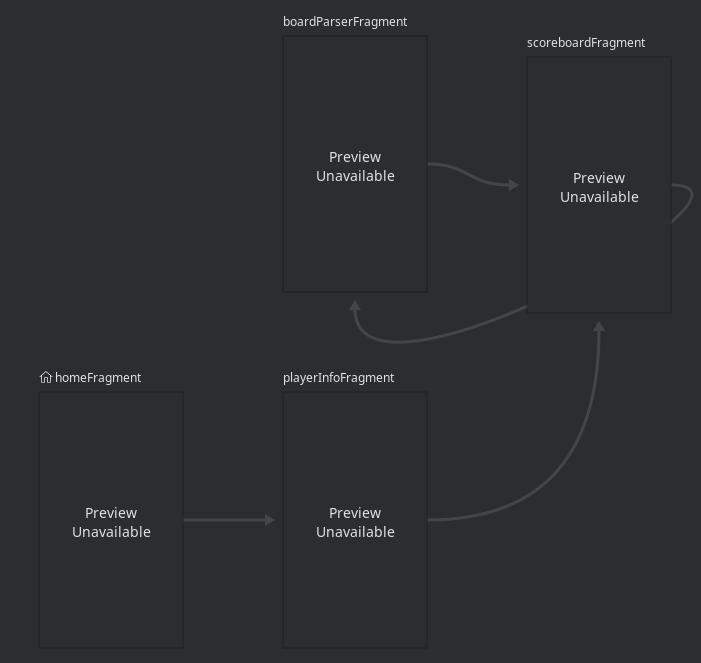

The Android application uses a single activity, with a Nav Graph to link fragments. A game state manager passes necessary data across fragments.

The navigation graph is defined in the image below:

UI

Fragments are modular UI elements that encapsulate a portion of the interface. Each fragment corresponds to a screen in the app’s navigation flow.

The fragments used are as follows:

homeFragment- This is the home screen, players can start a new game from here.

playerInfoFragment- Responsible for collecting input for the number of players and their names.

scoreboardFragment- Displays current game scores. Allows navigation to the board parsing view to score a new move.

boardParserFragment- Opens a camera stream, performs neural network inference, and updates board state. The detection, classification, and other vision is described in Board Parsing Pipeline

State Management

A ViewModel, GameStateManagerViewModel, retains and updates necessary game state information across fragments. This includes player count, names, current turn, score, and the board state. Because fragments have varying lifecycles as well as background threads running important logic, state has to be managed asynchronously and lifecycle-aware to avoid any inconsistency and to avoid race conditions.

In the board parser, neural network inference runs on a background thread. When updating the board state from it’s output, thread safety is required to ensure the proper state is passed to the ViewModel. Specifically, the app uses MutableLiveData in the game state manager to do this. postValue() allows background thread processing to update variables in a safe manner. Observers registered to the corresponding LiveData are notified on the main thread, ensuring other components update without error.

The GameStateManagerViewModel also contains validation and scoring logic described in Scoring.

Performance

When the board parsing fragment is active, the pipeline averages about 10 frames per second, around 100ms per frame.

Training

Training Corners

YOLOv10-n was trained through the Ultralytics Python library.

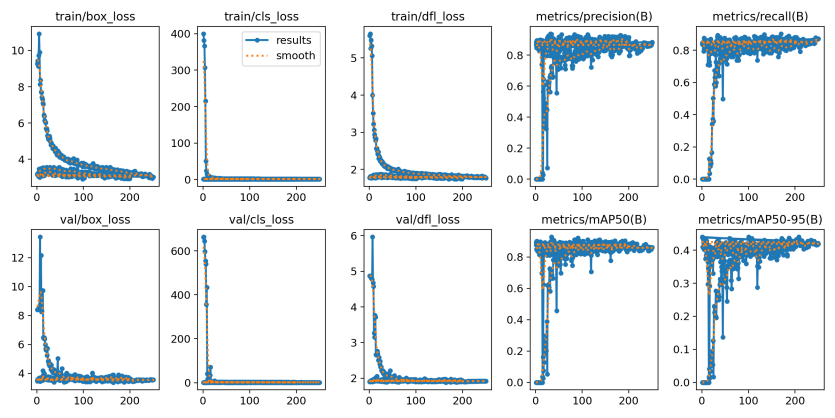

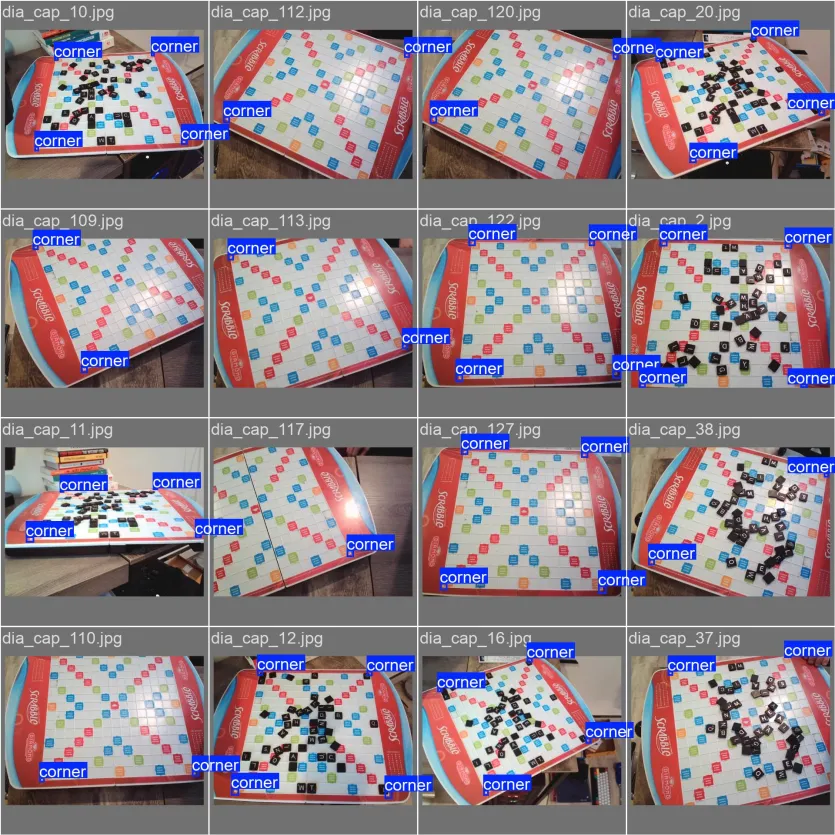

Data

Over 400 images of a scrabble board were used to train. Images were taken from a variety of angles, distances, and room lighting conditions. Then, the images were resized to 640x640.

Images are labelled with a small, tightly fitting bounding box around each of the corners.

After initial training, the corner detections worked great. However, it was unable to detect corners when tiles were placed on the corner cells. This was due to having no examples in the training set with tiles on those cells.

Hyperparameters/Augmentation

The dataset was divided into a 80/10/10 train/val/test split.

- Epochs: 250

- Trained extensively to improve mean average precision (mAP) in later epochs.

- Batch Size: 32

- Image Size: 640x640x3

Training hyperparameters are as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

lr0: 0.01 # default initial learning rate

lrf: 0.01 # default final learning rate

momentum: 0.937 # default momentum

weight_decay: 0.0005 # default weight decay

# simulate board rotations

flipud: 0.5

fliplr: 0.5

# simulate different board perspectives

degrees: 45.0

perspective: 0.001

shear: 45.0

scale: 0.5

# simulate different lighting conditions

hsv_s: 0.9

hsv_v: 0.9

# disabling defaults

translate: 0.0

mosaic: 0.0

crop_fraction: 0.0

Results

During training the loss successfully converged and generalized well to the validation set.

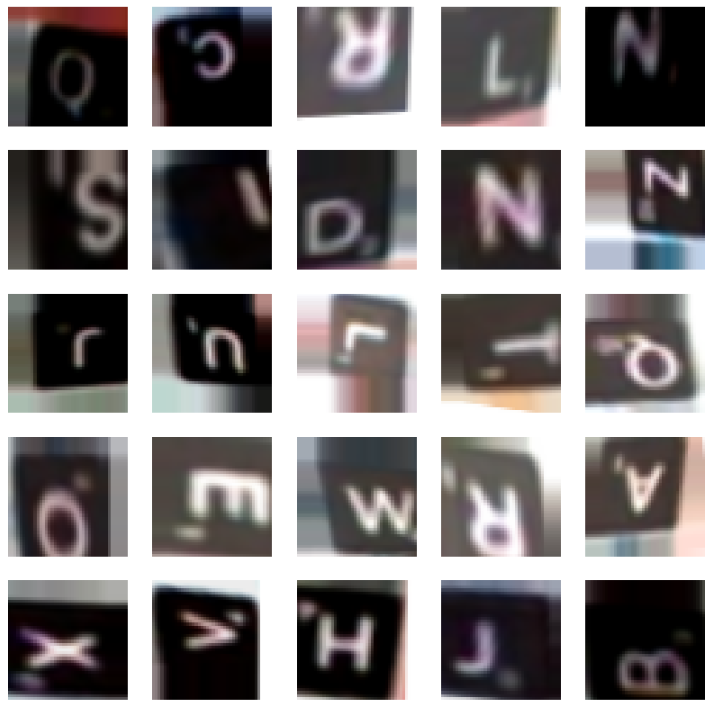

Training Tiles

The tile classification CNN was trained via Keras in Python.

Data

Tiles were captured with a script that enabled quick and simple labelling using the output image from Figure 2. Images/labels were saved by clicking on a cell, and then pressing the respective key on the keyboard. To keep track of previously labelled cells, they are marked with the labelled letter. Pressing spacebar removes the marks, resetting the board to continue labelling.

For each labelled board, only one of each tile was placed. This evenly distributes samples, preventing bias.

All tile orientations on the board were also captured from the 4 different rotations, 0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°. This allows for classifying a board from any of those rotations, as well as building a more robust dataset.

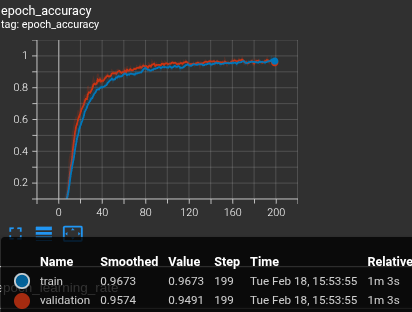

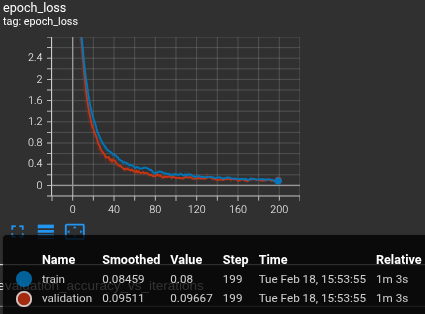

Hyperparameters/Augmentation

The dataset was divided into a 80/10/10 train/val/test split.

- Epochs: 200

- Batch Size: 32

- Image Size: 42x42x3

Simple augmentations were applied simulating different lighting conditions.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

augment = keras.Sequential(

[

layers.RandomContrast(0.6, value_range=(0.0, 255.0)),

layers.RandomBrightness(0.3, value_range=(0.0, 255.0)),

layers.RandomFlip("horizontal_and_vertical"),

],

name="augment",

)

Results

During training the loss successfully converged and generalized well to the validation set.

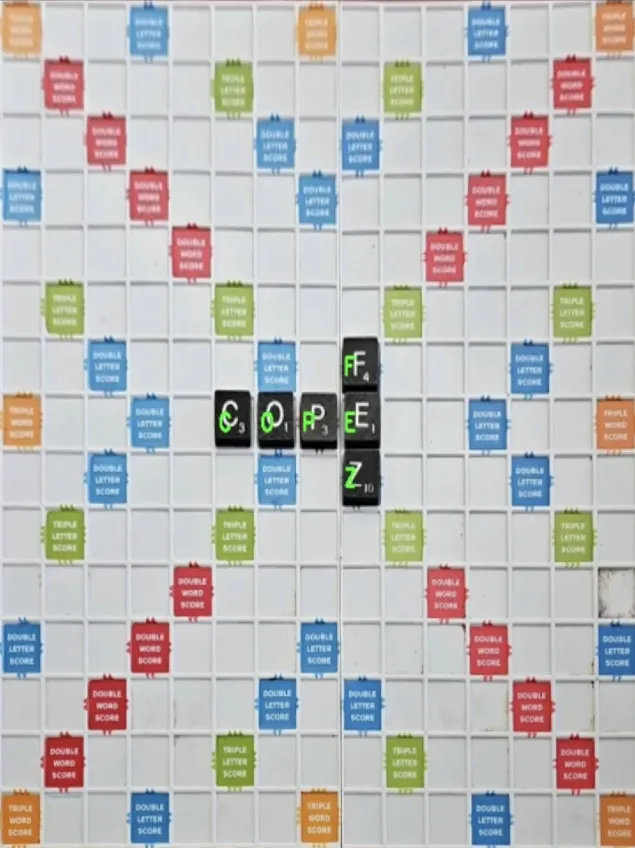

Gameplay

Here is a gif showcasing the app.

Prior Approaches

React Native

Initially, I wanted to create a cross platform application. However researching more about what would be necessary with custom C++ modules to run neural networks natively on both devices, it was decided to avoid the extra complexity due to the time constraint of this project.

YOLOv8

YOLOv8 was initially trained and used through Keras, however after moving the code to run on mobile, it was apparent how the Non-Maximum Suppression would hinder performance. Moving to Ultralytics also allowed usage of YOLOv10.

Inference Runtimes

- OpenCV Deep Neural Network library

- This was initially tried with YOLOv8, but there was a significant lack of support with various operations and layers. It did however have great support for older models.

- ONNX Runtime

- ONNX was initially tried, however the library has poor device support, and it was unable to run any operations on the GPU.

Constraints

Board/Tiles

Only the Hasbro Diamond Edition Scrabble board and the black tiles it comes with can be used with the current state of the project. To simplify, I opted to use only a single type of board and tile as I only own one scrabble set and collecting training data for multiple would have been time consuming.

Lighting

The vision system sometimes struggles in poor lighting environments, such with colored lighting or dark rooms.

Future Work

Word Validation

Currently there is no way to challenge the other player’s moves against a dictionary. For competitve games this would be an important feature.

Performance

The performance of the board parser can definitely be improved. Smaller neural networks and more efficient algorithms would be a start. Using a network designed for mobile, such as MobileNet could also be an option.

Scoring Moves Without a Capture Button

By pointing the phone at the board without pressing capture, friction when using the app would be further reduced. This could potentially be done by automatically approving a board to be scored as soon as the four corners come into view.

Different Game Sets

Accounting for different boards or tiles is a natural evolution of the project. This would require more training data for corner detection as well as tile classification. An issue with different tile colors is the masking stage that is used before classification. A solution would be a calibration setting where the color of the tile can be set before gameplay.

Visual Board in Application

Although the classification is generally robust, mistakes still can happen. Adding the ability to view the current board state and edit any mistakes would be a great quality of life feature.

Google Play

I soon plan to publish this application on the Google Play store.

Storing and Viewing Previous Games

Viewing game history is a great way to improve and see progress over time.

Expanding to Other Applications

While this system is designed for scrabble, modularity enables a straightforward way to modify it for other applications. For other board games, such as chess, the minimum required would be different training data and some changes to the move engine.

Conclusion

ScrabbleCV achieves real-time scoring of Scrabble moves using on-device computer vision and neural networks. The system performs reliable board detection and tile classification from arbitrary camera positions. The architecture is modular and can be extended to other board games or applications. The goal of a real-time, computer vision scrabble scoring app was successfully met.